Getting

Started

[Genhelp | Program Manual | User's Guide | Data Files | Databases | Release Notes ]

Table of Contents

Overview

Fundamentals: Using UNIX

Getting help for UNIX

Logging on

Working with directories

Displaying directory contents

Creating directories

Changing directories

Defining and using logical names for directories

Working with files

Creating and editing files

Specifying files

Deleting files

Displaying and changing file protections

Using wildcards

Viewing files

Using command line redirection

Controlling program execution

Running jobs in the background

Displaying background jobs

Moving a job to the foreground

Terminating a background job

Logging off

Quick reference

UNIX commands

Controlling screen output

Getting started with GCG

Initializing GCG

For advanced users

Customizing your login

Initializing GCG

Automating program commands

Overview

This section helps prepare you to use

Accelrys GCG (GCG). Written with the novice user in mind, it

provides you with the fundamentals of working with the UNIX operating system.

While the commands and procedures in later sections and in the Program Manual

often assume that you have a working knowledge of UNIX commands, this section

assumes you have little or no experience working with the computer, and it

provides you with that basic groundwork.

You can find

details on working with files and directories, logging on and off the system,

and customizing your login environment in this section. It also explains how to

start running GCG.

GCG is

installed on a computer using a UNIX or Linux operating system. You can connect

to that computer in one of two ways: 1) you are directly connected to the

computer, or 2) you connect to the computer over the network. The device you

are using could be a dumb terminal, a console, an X Windows terminal, or a PC

or Macintosh running terminal emulation software. Regardless of what device you

are using to access GCG, you must become familiar with UNIX commands to use

GCG programs and manipulate the output.

Fundamentals: Using UNIX

Your system

manager has just set up a UNIX account for you to use the GCG. But what if

you've never used UNIX before and you're not sure where to start? This section

will walk you through the basics of using the UNIX operating system. If you

take a little time now to learn the basics of UNIX, you will increase the

efficiency with which you can later work with GCG.

This section

teaches you how to

- Get help for UNIX.

- Log on.

- Work with directories.

- Work with files.

- Customize your login.

- Use command-line redirection.

- Control program execution.

- Log off.

- UNIX commands are case sensitive. That

is, uppercase commands are distinguished from lowercase commands which are

distinguished from mixed case commands. Type carefully!

- Some UNIX commands require input

files. For example, rm (remove)

requires the name of the file to be deleted.

- UNIX commands support parameters,

also known as command-line switches, which modify the action of the

command. You precede parameters with a space and a dash (-), and you can

use multiple parameters to modify a command. For example, consider the

command % ls -l -a.

The -l

parameter modifies the command ls

(list) to display each file in your directory with its file protection

(read, write, execute) information. The -a parameter modifies the

command to list all files in your directory, including those that begin

with a period.

It is beyond

the scope of this manual to provide detailed instructions in the use of text

editors. However, we do provide the basics to get started using vi in Appendix B, Text Editor Basics. For more information

about the default text editor vi, see the

documentation for your UNIX system. For other text editors, see the appropriate

program documentation.

Getting help for UNIX

To access

online help for UNIX commands:

Type % man command_name.

For example, % man ls

displays online help for the UNIX command ls (list).

The UNIX

commands are also described in detail in your UNIX operating system manuals. For

more information, see your system manager.

Logging

on

To use GCG, you will be in one of two possible situations: 1) you are directly

connected to the computer, or 2) you connect to the computer over the network.

The device you are using could be a dumb terminal, a console, an X Windows

terminal, or a PC or Macintosh running terminal emulation software.

To log on

to a UNIX machine:

Note:

You must have an approved account, also called a login, from the system manager

to use any UNIX computer. The system manager usually sets up a user name, which

is typically your first or last name, and lets you specify a password for

security. No one can access the system through your account without your

password. Keep your password secret.

- Because each site is different, ask

your system manager for instructions on how to connect to the UNIX

computer.

When

you are connected, you should see the prompt "Login:" on the screen.

If you don't, press <Return> until the prompt appears.

- Type your user name and press

<Return>. The system displays the prompt "Password:".

Note:

Your user name and password are case sensitive; that is, the computer

distinguishes uppercase letters from lowercase letters. Therefore, type your

login name and password exactly as they are set up in the system.

- Type your password and press

<Return>. For security, you will not see your password appear on the

screen as you type. The system welcomes you and logs you in.

Note:

If you make a mistake in typing your user name or password, press

<Delete> to delete the error or press <Return> and try again.

When

you see the operating system prompt (%) in the left margin of your screen,

the computer is ready for your commands. Note that the % prompt is a convention used in this

guide. Your site may have set up a different prompt.

Working with directories

You can

think of a directory as being similar to a file cabinet. Within the file

cabinet you can find drawers (or subdirectories) and files. Subdirectories,

like file cabinet drawers, help you organize your files into loosely related

groups.

When you log

in, you will be in your top directory, also known as your home directory. Your

current (or working) directory refers to whatever directory you are presently

working in.

For more

information on working with directories and UNIX commands, see the

documentation for your UNIX operating system or your system manager.

Displaying directory contents

To display

the contents (that is, the files and subdirectories) of your current directory:

Type % ls

(list).

To display

what directory you are currently working in:

Type % pwd

(print working directory).

Creating directories

Your system

manager probably provided you with one directory in which to maintain your

files--your home directory. To help organize your files, you may want to create

subdirectories within your current directory.

To create a

subdirectory:

- Move to the directory in which you

want to create a subdirectory.

- Type %

mkdir subdirectory,

for example % mkdir project.

The subdirectory project appears in your current directory.

Changing directories

You've

learned how to create directories, and now you want to know how to move between

them. Consider the following example of a directory tree as you read through

the tasks below.

To move

from one directory to another:

Choose from

the following.

- Use the complete file specification,

also known as the absolute pathname, to move to a different directory. For

example, if your current directory was Patterson, you could change

directories by typing % cd /users/smith.

- To move down from your current

directory, type the relative path specification, % cd subdirectory.

For example, if you are in the directory /users/smith, you could type % cd project

to move down one directory or % cd project/data

to move down two directories.

- To move up one directory, type % cd

.. The ".."

always signifies the parent directory.

- To move to a parallel directory,

type % cd

../directory.

For example, if your current directory is /users/smith/project and you

want to change to the directory /users/smith/test, you would type % cd

../test.

- To move to another user's home

directory, type % cd ~username.

For example, to move from the Patterson directory to the Smith directory,

type % cd ~smith.

- To move to your home directory, type

% cd.

Note:

The following commands are only available when GCG has been initialized (see Getting Started with GCG in this section for

more information). They are not standard UNIX commands.

- To move down one directory, type % down subdirectory,

for example % down project.

- To move up one directory, type % up.

- To move to a parallel directory,

type % over subdirectory.

This command takes the place of first moving up one directory and then

back down to a different directory. For example, if you are in the

directory called /smith/project and you want to move to the /smith/test

directory, you could type % over test.

- To move to your top (or home)

directory, type % home.

- To move to a relative directory, or

to a directory defined by a logical name, type % to directory

or % to logical_name.

For example, % to gendocdata

moves you to a directory with the logical name gendocdata,

where you can find alternative GCG sample sequence files.

Defining and using logical names for directories

If you move

to a directory other than your home directory often, you can assign it a

logical name. A logical name is a shorthand name you can give a filename or

directory. Logical names often reduce typing and are easier to remember than

full specifications. The GCG utility name lets you create logical names

within a UNIX operating system.

For example,

let's say you assigned /smith/project the logical name proj.

Regardless of the directory you are located in, you can move to /smith/project

with the command % to proj

instead of typing the entire directory specification.

Note that

before you define a logical name, you should first check to make sure you will

not overwrite an existing logical name. To do so, type % name logical_name.

GCG

programs use logical names to refer to various resources in the UNIX file

system. These resources consist of directories, databases, system utilities,

shell scripts, devices, or files. For example, the logical name genrundata is assigned to the directory containing the

sequence databases and other data files. The logical names and their

specifications are maintained in a table you can view by typing % name.

To define

logical names for directories:

·

Open the $GCGROOT/etc/dirs.conf

file which contains all the logical names of GCG. Only the System manager can

define all the logical names in this file.

Note: In

Note: Logical names are case insensitive; that is, they can appear in

uppercase, lowercase, or mixed case. For example, the logical name GenDocData is the same as gendocdata.

· In

a single line, type the logical name you want to set, for example, proj. Follow this with the directory specification of the

resource for which you want to define the logical name, for example, /smith/project.

Note that directory specifications are case sensitive.

· Save

the file (dirs.conf) and exit.

To specify

a directory logical name:

Type the

logical name optionally followed by a colon and a filename, for example proj:gamma.seq.

You must use a colon (:) between a directory logical name and the filename that

follows it.

If you

forget what the logical name is defined as, then type % name logical_name.

For example: % name proj/smith/project.

Note:

Since the logical names are created within the

Working with files

Files are

where you store information in the computer. For example, sequence information

or the output of a program. Most GCG programs require one or more files as

input and produce an output file of results.

Filename

Conventions

Filenames

have a particular format: /directory/filename, where directory is the directory

in which the file belongs; and filename is the name of the file. Directory

names and filenames are case sensitive. You can use all alphanumeric characters

as part of the name; however, you should avoid using characters with special

meaning in UNIX, such as / \ " ' * ; - ? $ [ ] { } ~ ! < >. In

addition, avoid including spaces within the name. Try to make the directory or

filenames as descriptive as possible to help you remember their contents.

Unlike some

other operating systems, UNIX doesn't assign file extensions to distinguish

types of files. You can, however, add your own extensions to group similar

types of files together. GCG often adds extensions to help distinguish

output files.

Note that

UNIX saves only the most recent version of a file. Therefore, use care in

saving and naming files: if the filename already exists, the system writes the

new information over the existing file without warning you. All previous

information is lost.

For more

information on working with files and UNIX commands, see the UNIX documentation

for your system or your system manager.

Creating and editing files

Most GCG

programs create output files, some of which you can use as input to other

programs. To create files in a directory, you must have privileges to write in

that directory (see "Displaying and Changing File Protections" in

this section). If you don't, change the directory protections (if possible) or

move to another directory in which you do have the necessary privileges.

We recommend

that you learn to use a text editor to create and edit files. Files written by

most GCG programs are easily edited using text editors.

To create

and edit files:

Use a UNIX

text editor, for example vi. You can use other text editors as well. For more

information about vi, see Appendix B, Text Editor Basics or refer to the

documentation for your UNIX operating system. For more information about other

text editors, see the appropriate program documentation.

Note:

If you create and save a file under a filename that already exists in the

directory, UNIX replaces the original file with the new information. That is,

UNIX writes over the data in the original file without warning you.

Specifying files

UNIX and GCG commands often require one or more filename(s) to do their job. A simple

example of a UNIX command is when you type % rm,

the computer expects you to supply it with the name of the file to remove. As

an example of a GCG command, when you run the Map+ program, it asks you

"MAP of what sequence?" In such instances you need to specify a

filename.

To specify

a file to a program or command:

Choose one

of the following.

- Files in your current

directory. If the file is in your current directory, type the

filename, for example gamma.seq.

- Files in other directories.

If the file is in a directory other than your current directory, type the

entire file specification, for example /smith/project/gamma.seq. If the file is in a

subdirectory of your current directory, use the relative file

specification, for example project/gamma.seq.

When you are using GCG commands, you can use logical names within the

specification, for example share_tfsites:tfsites.dat.

Note:

For more information about directories, see "Working

with Directories" in this section.

Deleting

files

You will

find it necessary to clean up your directories at times and to delete unnecessary

files. You can do this with two commands: rm

(remove file) and rmdir

(remove directory).

To delete

files from a directory:

Choose from

the following.

- rm. Type % rm filename

where filename is

the name of the file(s) you want to delete. For example, % rm gamma.seq

deletes a file named "gamma.seq" in

your current directory; % rm gam*

deletes all files beginning with "gam."

- rmdir.

Type % rmdir directory_name

where directory_name

is the name of the directory you want to delete. For example, % rmdir project

deletes the "project" directory from your current directory.

Displaying and changing file protections

File

protection is a means of security by which three categories of users are

assigned privileges to each file: user (you), group (the group(s) you belong

to, for example your lab), and other (everyone outside your group). Each

category has certain privileges of access and use:

(r) read -

Users can read the contents of the file or directory.

(w) write -

Users can write in and edit the files or directory.

(x) execute

- Users can execute the file or files in the directory or can

display the contents of the directory.

To display

protections for files in your current directory:

Type % ls -l.

The system

displays the name of each file followed by the protections (rwx)

grouped by user, group, and other. For example

As you can

see in this example, directories as well as files have protections assigned to

them.

To change

file protections:

Type % chmod u=protections filename,

where u defines the category of user (u [user],

g [group], or o [other]) and protections

defines the protections you want to set (r [read], w [write], or x [execute]).

Using

wildcards

Use

wildcards to specify multiple files. An asterisk (*) wildcard serves as an ambiguous

replacement for one or more characters; the * means "anything or

nothing." You can also use a percent sign (%)

wildcard as an ambiguous replacement for a single character. Consider the

following examples:

- Bov* includes all files that begin with

"Bov".

- gamma%.seq includes all files

that contain "gamma" followed by a single character, for example

gamma1.seq.

- % ls *.seq

displays all files in your current directory with the extension ".seq".

- % cp *.* /smith/project copies

every file in the current directory to the directory /smith/project.

Most UNIX

commands and some GCG programs accept wildcards in file specifications.

Note:

If a command allows two file specifications on the command line, never use

wildcards in the second parameter, for example % cp *.txt *.seq. Using

wildcards in this manner will produce unexpected results.

Viewing

files

To view the

contents of files:

Choose from

the following.

- cat. To display the entire contents

of a file, type % cat filename, for example % cat gamma.seq.

- more. To display the contents of a

file screen by screen, type % more filename,

for example % more gamma.seq.

Press the <Space Bar> to advance from screen to screen. Press q to exit more and return to the command

line.

Using command line redirection

Every UNIX

program or command can read or write to:

- Standard input. The

stream from which a command takes its input, such as from the terminal, a

file, or the previous process in the command line.

- Standard output.

The stream to which a command sends its output, such as to the terminal, a

file, or the next process in the command line.

For example, "piping" ( | ) means redirecting the standard output of one program to the standard input of another. - Standard error. The

stream by which a command sends error messages, such as the terminal, a

file, or to the next process in the command line.

The table

below describes the command line characters you can use to redirect standard

input, output, and error. Notice that you can combine input and output

redirection characters on the command line.

|

Task |

Character |

Example |

Definition |

|

Redirecting

|

< |

% sort < unsorted.txt |

The

Sort program uses the file unsorted.txt as standard input.

Standard output is displayed on your screen. |

|

Redirecting

|

> |

% sort < unsorted.txt > sorted.txt

|

The

Sort program uses the file unsorted.txt as standard input and

writes standard output in the file sorted.txt (instead of on your screen). |

|

Redirecting

|

>&

(csh) |

% sort < unsorted.txt >& sorted.txt

|

The

Sort program uses the file unsorted.txt as standard input and

writes standard output and standard error in the file sorted.txt. |

|

Appending

|

>> |

%

sort < unsorted.txt

>> sorted.txt |

The

new data in the file sorted.txt is added to the end of an

existing file, if there is one. This prevents existing data from being

overwritten. |

|

Piping

|

| |

% sort < unsorted.txt | more |

The

output of the Sort program is used as standard input to the More program. |

Controlling program execution

With UNIX,

you can run several programs at once from the same terminal. UNIX allows you to

do this by running programs in the foreground or background.

- Foreground jobs. A

foreground job allows you direct input from the keyboard. You can have

only one job running in the foreground; the terminal cannot be used for

another job until the current foreground job finishes.

- Background jobs. If

a job is running in the background, the system is working on it out of

view, freeing your terminal for other work. You can have multiple jobs

running in the background.

The

ability to put jobs in the background is very useful; it allows you to keep

working at your terminal even though you are running one or more programs which

take some time to complete.

If

you want to run one or more jobs in the background, keep the following points

in mind:

- You can't give

background jobs input from the terminal or keyboard. Thus, if a program

you are running has prompts which require your input, it will stop when

it reaches the first unanswered prompt. Therefore to run such programs,

you must use the necessary command-line parameters which answer those

prompts and allow the program to run to completion.

In

GCG, you can bypass most program prompts by using parameters on the command line.

For more information on using command-line parameters, see "Using Program

Parameters" in Section 3,

Running Programs.

- If a foreground

job typically sends output to the terminal screen, it also will do so

when it is a background job. Therefore, to avoid output scrolling on your

screen from a background job while you are working on a foreground job,

redirect the output from the background job into a file.

Running jobs in the background

Although you

can run only one program in the foreground, you can run multiple programs in

the background.

To run a

job in the background:

Add an &

(ampersand) to the end of the command line, for example % fasta ggammacod.seq

-Default &.

The system

puts the job in the background and displays a response similar to the

following:

[1] 14999

%

The number

in square brackets [ ] is your job number, in this case job number 1. If you

ran a second job in the background, it would have a job number [2]. The second set of numbers is the

process identification (PID) number assigned by the system. The system prompt (%) tells you the system is ready for your

next command.

A job will

stop running if it needs information that you must enter at the keyboard, such

as a filename or other parameter. When this happens to a background job, the

system displays a message similar to the following on your screen:

[1] + Stopped (tty input) fasta

To continue the job, bring it to the foreground. The job, requiring your input,

continues from where it stopped. For more information, see "Moving

a Job to the Foreground" in this section.

If you log

out while running a background job, the job continues to run. When the job

finishes processing, its output file appears in the directory you specified.

Note:

Some programs, such as those that search the databases, are computationally

intensive and take some time to execute. You can use the -Batch parameter to submit these

programs to the batch queue to execute at a later time. For more information

about the batch queue, see "Using the Batch

Queue" in Section 3,

Using Programs.

Displaying background jobs

To see a

list of all jobs currently running:

Type % ps-aef\grep <program name>. A list of each background job you are

running appears on your screen, marked as either running or stopped. A running

job is executing in the background. A stopped job is one that either you or the

system put on hold. For example

[1] +Running (set noglob;

$GCGUTILDIR/fasta ggammacod.seq

-def)

[2] -Stopped (set noglob; $GCGUTILDIR/mfold -save ala-trna.seq -def)

Moving a job to the foreground

Let's say

you ran a program and put it in the background. But the program stopped after

encountering an unanswered prompt. What do you do? You can move the program

into the foreground. The program continues from where it left off in the

background.

To move a

background job to the foreground:

1.

Type % ps-aef\grep <program name> to see a

list of the jobs running in the background.

2.

Type % fg %job_number, where job_number is the number

appearing between square brackets [ ] in the job listing. For example, % fg %2

brings job number 2 into the foreground.

You can put

a foreground job in the background again by pressing <Ctrl>z to stop the

job then typing % bg

(background) to put it in the background for processing. The job will continue

running in the background

Terminating a background job

To terminate

a background job:

1.

Type % ps-aef\grep <program name> to see a

list of the jobs running in the background.

2.

Type % kill: job_number,

where job_number

is the number appearing between square brackets [ ] in the job listing. For

example, % kill %2 terminates job number 2.

Logging

off

To end a

session with a UNIX system and log out:

Type % logout.

Note:

If you are running a program in the background from csh

when you log out, and you redirected the output to a file, the program runs to

completion and places the output file in the directory you specified. However,

if you haven't directed your output to a file, when you log out, the program is

terminated before completion.

Quick

reference

UNIX

commands

You should

become familiar with the following UNIX operating system commands to use the

UNIX system and GCG programs effectively and efficiently. For more

information on UNIX commands, see the documentation for your UNIX operating

system.

|

Command |

Example |

Description |

|

% cat filename1 filename2 > new_filename |

% cat temp.txt gamma.seq

> new.seq |

Combines

the temp.txt and gamma.seq files and creates a new

file, new.seq, with their contents. |

|

% chmod u=protections

filename |

% chmod u=rwx temp.txt |

Changes

the users (u) protections (r=read, w=write, x=execute) on a file. |

|

% cp filename1 filename2 |

% cp gamma.seq temp.txt |

Creates

a file called temp.txt that contains the same data as the gamma.seq

file. If a file temp.txt already exists, it is overwritten. |

|

% finger username |

% finger smith |

Displays

the shell you are using as well as other information. |

|

% grep character_pattern

filename |

% grep smithies gamma.seq |

Looks

through gamma.seq for the character pattern

smithies and displays the lines that match the pattern. The character_pattern

and filename are

case sensitive. |

|

% logout |

% logout |

Ends

your session with UNIX. |

|

% ls |

% ls |

Lists

all of the files in your current directory, except those beginning with a

period (.). |

|

% ls –parameters |

% ls -a |

Lists

all the files in your current directory, including those beginning with a

period, for example .login. |

|

% ls /directory |

% ls /smith/project |

Lists

all the files in the /smith/project directory, except those beginning with a

period. |

|

% man command |

% man ls |

Displays

online documentation for the ls

command. The -k

parameter displays all commands related to the keyword you provide. This is

useful if you remember a command's function but do not remember the command

name. |

|

% mkdir subdirectory_name |

% mkdir project |

Creates

a subdirectory called project under your current directory. |

|

% more filename |

% more gamma.seq |

Displays

the gamma.seq file on your terminal, one screen at

a time. Press the <Space Bar> to advance screen by screen. |

|

% mv filename1 filename2 |

% mv gamma.seq

temp.txt |

Changes

the name of the gamma.seq file to temp.txt, writing

over the contents of temp.txt, if it already exists. |

|

% pwd |

% pwd |

Displays

the full path of your current directory. |

|

% rm -i

filename |

% rm -i

gamma* |

Deletes

all files in your current directory that begin with the characters gamma. The

-i

parameter makes you confirm the deletion. |

Controlling screen output

The

following is a partial list of key combinations you will find helpful in

controlling screen output. For more information on terminal keyboard

combinations, see the documentation for your UNIX operating system.

|

Control

Key |

Description |

|

<Ctrl>c |

Cancels

a program or an executing UNIX command. |

|

<Ctrl>o |

Suppresses

screen output without stopping the program. |

|

<Ctrl>z |

Suspends

a job. Typing % fg %job_number brings the suspended job to

the foreground where you can work with it again, for example % fg %6.

If you cannot remember what programs you suspended, type % jobs to list the jobs and job

numbers. |

|

<Ctrl>s |

Stops

screen output from scrolling off the screen. |

|

<Ctrl>q |

Resumes

screen output that has been stopped by <Ctrl>s. |

|

<Ctrl>u |

Deletes

text from the cursor to the beginning of a line. |

|

<Ctrl>r |

Refreshes

the line while typing a command. |

Getting

started with GCG

Note: Sections 2-5 in this guide provide general instructions for

all programs in GCG. For detailed instructions about a specific program, see

the Program Manual.

Initializing GCG

To use GCG, you must first initialize your environment. Initializing your

environment gives you access to GCG programs, the databases, data files the

programs need, logical names, and other information required for the Package to

run smoothly.

To initialize GCG:

To initialize GCG type the following

on the command line:

% source <Installed directory

Path>gcgstartup

% gcg.

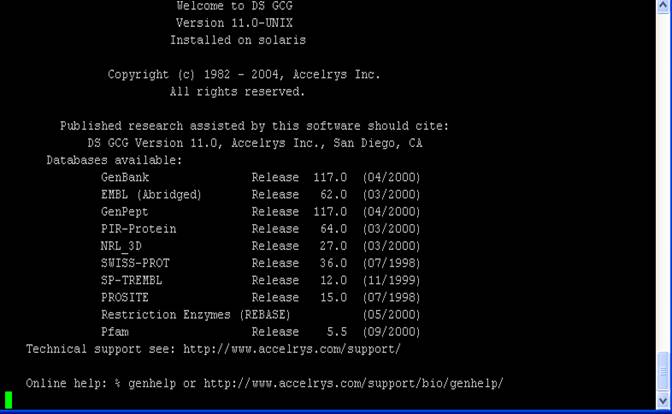

The system takes a few seconds to initialize GCG and displays a banner

similar to the following:

The banner displays the version of the package you are running, as well as

the reference you can cite if you use GCG in your publishable research.

(Because the banner changes with each update to the available databases, your

banner may look slightly different than the one above.)

When you see the operating system prompt (%),

GCG is ready for use.

Note:

Some of the programs like motifs and prime in GCG are resource intensive. To

make sure these have enough resources in the system to run, you can try running

unlimit before you run these programs.

% unlimit

Note: The % prompt is a convention used in this guide.

Your site may have set up a different prompt. Also, if the above commands do not

initialize GCG on your system, see your system manager. For more

information, see the section “Configuration” in the section “GCG Environment”

in the System Support Manual.

For help working with GCG, check the documentation, look in the GenManual

or GenHelp online help, or contact technical support. For more information, see

"Getting Help" in

the preface "Before You Begin."

TIP - If your primary reason for using the UNIX system is to use GCG, you may want to customize your login to automatically initialize it. To do so, you need to create or edit your .login or .profile file. For more information on working with login initialization files, see "Customizing Your Login" in the "For Advanced Users" section of this section.

For advanced

users

The information in this section is intended for users who are familiar with

the operating system. This section teaches you how to

- Initialize GCG in your

login.

- Automate program commands

in your login.

- Define logical names in

your login.

- Define your graphics

configuration in your login.

Customizing

your login

You or your system manager can customize your login to ensure that certain

commands execute or are available every time you log in. For example, you may

want to customize your login to automatically initialize GCG. Or, you can

assign logical names for filenames and directories so that each time you log

in, they will be defined automatically. To do these things and more, you can do

this with two files:

Note: To determine which shell your system runs under, type % echo $SHELL.

- .login (csh) or .profile (ksh).

A shell script that defines your UNIX user environment. For example, if

your primary reason for using UNIX is to use GCG, you may want to

customize your login to automatically initialize it. UNIX executes the

.login or .profile file each time you log in.

- gcgrc (csh)

or .gcgrc.ksh (ksh).

A shell script that defines your aliases for GCG programs and operating environment. For example, if you find that you

frequently use a program with the same parameters, you can define an alias

as a shortcut command for the program and parameters. (For more

information about shell scripts, see "Working

with Shell Scripts" in the "For Advanced Users"

section of Section 3, Using Programs.)

When you initialize GCG environment, the last step

in the initialization process is the execution of the aliases (csh) or aliases.ksh (ksh) file present in the $GCGROOT/etc directory. This file

is not executed until after the logical name and symbols are fully initialized.

Because of this, the aliases (csh) or the aliases.ksh file is the best place to put your customized

commands.

Note: The

aliases (csh) and aliases.ksh

(ksh) can be modified by the sytem

administrator only.

Apart from system aliases, which are automatically

sourced by GCG Environment, you can define your own aliases and source that

file separately after initializing GCG Environment.

Note: The aliases set

by $GCGROOT/etc/aliases (csh) or $GCGROOT/etc/aliases.ksh can be

overridden if you have written your own aliases file in your local environment.

You should be careful not to override the aliases already defined in the $GCGROOT/etc/aliases

(csh) or the $GCGROOT/etc/aliases.ksh file.

To create a .login (csh) or .profile(ksh) , aliases (csh) or aliases.ksh (ksh) file:

Use a text editor of your choice, for example vi.

Create the file(s) in your top directory.

Note: To test your login file after you've edited and saved it,

type % source filename (csh) or % . filename (ksh), for example %

source

.login (csh) or % . .profile (ksh). The

system reruns the file.

Initializing GCG

To set up your login to automatically initialize GCG:

- Open your .login (csh) or .profile (ksh) file

in the text editor of your choice, for example vi.

- Use the following as an

example of what to type:

(csh)

%

source <Installed directory Path>gcgstartup

% gcg

% source .gcgrc

(ksh)

% . <Installed directory Path>gcgstartup

% gcg

% . .gcgrc.ksh

Note: The first line of each of the csh and ksh examples sets

environment variables for working with GCG. See your system manager for the

correct specification at your site.

The second line of each of the examples initializes the Package.

- Save the file and exit

from the text editor.

Note: For more information,

see "Working

with Shell Scripts" in the "For Advanced Users" section of

Section 3, Using Programs.

Automating

program commands

You may find that you frequently run a GCG program using the same

parameters each time. You can define an alias in your aliases (csh) or aliases.ksh (ksh) file to create a shortcut command for the program and

its parameters.

Before you create an alias, you should check to make sure the alias is not

already defined. To do so, type % alias

alias_name. Then (if the alias is not defined, or

if you want to redefine the alias) use the following syntax to define an alias:

% alias command_line

If you define an alias at the operating system prompt, it will be in

effect until you log out. To save your alias from one session to the next, add

it to your aliases (csh) or aliases.ksh

(ksh).

To define an alias:

- Open your aliases.ksh (location: $HOME) file in the text editor

of your choice, for example vi.

- Type the alias(es). For example, let's say you frequently run the MapPlot program with the parameter -CIRcular. To

create an alias, use the following as an example to write your own program

commands.

(csh) alias mc mapplot

-CIRcular

(ksh) alias mc=mapplot

-CIRcular

- Save the file and exit

from the text editor.

Note: Make sure the aliases.ksh file is

located in your top ($HOME)directory.

- Test the alias (es).

For csh, Type % source aliases or % source .login

For ksh, Type % . aliases.ksh or % . .profile

Type

the alias you assigned, for example % mc. The alias should run the specified

program and parameters (mapplot -CIRcular).

Defining logical

names

You can assign logical names to files you use frequently or directories that

you move to frequently. When you define logical names in your aliases (csh) or aliases.ksh (ksh) file, they are available every time you initialize GCG.

Note: Before you define a logical name, you first should check to make sure

the logical name is not already defined. To do so, type % name logical_name.

To define logical names in your aliases (csh) or aliases.ksh (ksh) file:

1. Open

the $HOME/.wp/dirs.conf file in the text editor of

your choice, for example vi.

2. On

a single line, type logical_name ~/directory,

for example

Proj ~/project.

The ~ (tilde) represents your

home directory.

3. Save

the file and exit from the text editor.

For more information on defining logical names, see the topic "Defining and Using Logical

Names for Directories" earlier in this section.

Defining your

graphics configuration

Before you run a GCG program that produces graphic output, you must

define your graphics configuration. Defining your graphics configuration means

telling the computer what graphics language you want to use and on what device

you want to display. For more information, see "Initializing

Your Graphics Configuration" in Section 5, Using Graphics.

Note: Before you start executing the steps given

below, read the file in the $GCGROOT/etc/symbol.conf

for the default graphics configuration that your system administrator has set

while installing and configuring GCG.

Note: You cannot change the graphics

configuration in $GCGROOT/etc/symbol.conf or in

$GCGROOT/etc/dirs.conf unless you have system

administrator privileges.

Note: If you need to change the graphics settings

in your local environment, you can do so by setting the required graphic setting

parameters in $HOME/.wp/symbol.conf and $HOME/.wp/dirs.conf or by defining these parameters in a aliases (csh) or aliases.ksh (ksh) file and source

the aliases file from your home directory

1. Open

your file $HOME/.wp/symbol.conf in the text editor of

your choice, for example vi.

2. Move

to the point in your file where you want to define the configuration commands.

1. On

a single line, type the commands you defined in step 1, separating each with a

single space. Most graphics configuration commands use the following format:

graphics_language graphics_device port_or_queue

where,

graphics_language is

the name of the graphics language you want to use. For more information about

what graphics languages are available, see "Configuring

Graphics Languages and Devices" in Appendix C, Graphics.

graphics_device is the

device you want to send output to, for example a graphics terminal screen,

printer, or plotter. Supported devices also are listed in "Configuring

Graphics Languages and Devices" in Appendix C, Graphics.

port_or_queue is where

the graphics device is attached, for example term

or /dev/tty11.

For example, to set up a graphics configuration

for a LaserWriter, you might type postscript

laserwriter /dev/tty11.

Note: Some graphics configuration

commands have fewer prompts, such as X Windows, and some have more, such as

HPGL. Make sure you answer all the prompts when you set up your graphics

configuration in your aliases (csh) aliases..ksh

(ksh) file.

TIP - "Initializing

Your Graphics Configuration" in Section 5, Using Graphics describes

using the SetPlot command to define your graphics configuration from the

command line. You also can use the SetPlot command in your aliases (csh) or aliases.ksh (ksh) file to define your graphics configuration for you

when you log in. To do so, follow these steps:

- Open your aliases (csh) or aliases.ksh (ksh)file in the text editor

of your choice, for example vi.

- Move to the point

in your aliases (csh) or aliases.ksh

(ksh) file where you want to define the

configuration commands.

- Type setplot graphics_device where graphics_device is the name

of one of the menu items when you run SetPlot.

- Save the file and

exit from the text editor.

- Source your aliases

(csh) aliases.ksh (ksh) file from your $HOME directory, so that the

custom graphics configuration will automatically be initialized.

[Genhelp | Program Manual |

User's Guide | Data

Files | Databases | Release Notes ]

Technical Support: support-us@accelrys.com, support-japan@accelrys.com,

or support-eu@accelrys.com

Copyright (c) 1982-2005 Accelrys Inc. All

rights reserved.

Licenses and Trademarks: Discovery Studio ®,

SeqLab ®, SeqWeb ®, SeqMerge ®, GCG ® and, the GCG logo are registered

trademarks of Accelrys Inc.

All other product names mentioned in this

documentation may be trademarks, and if so, are trademarks or registered

trademarks of their respective holders and are used in this documentation for

identification purposes only.